starstrewnsky

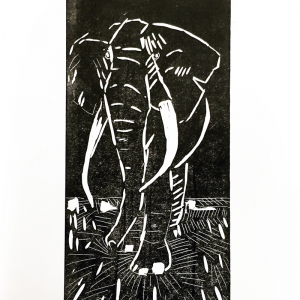

Elephant print

This is a linocut print, using ink and carving tools. It depicts a mature female Elephant on the African savannah.

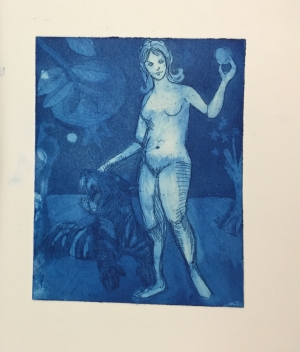

Aquatint print

This is a print made using aquatint. The process involves drawing on metal, etching texture onto the metal with wood dust, acid and wax, and using fire to temper and tame it at various points. All very laborious and exciting.

The image is of a nude female and her Tiger. Persephone, perhaps. In a pomegranate grove.

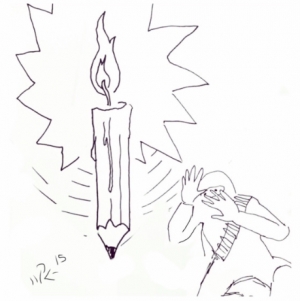

Drawing back

This is a cartoon I drew in a mangrove swamp in Sri Lanka, which is where I was when I heard the shocking news of the terrorist murders of innocent cartoonists, office workers and jewish shop workers.

I drew it in my notebook, then took a photo, edited it a little with SketchBook and when I was close to a wifi signal uploaded it to Instagram and my cartoon blog.

It was used by the Washington Post online.

Cartoons are not provocation for murder. God, if she exists, cannot be as pathetically insecure as those who believe they are.

Guitar songs

Artwork by Michael Fredman

I publish artwork in progress to my blog Art of Michael Fredman

Follow Michael's board My artworks in progress on Pinterest.

Cartoons by Michael Fredman

I publish cartoons to my blog isthissomekindofjoke.wordpress.com

A picture is worth a billion dollars

A picture is worth a billion dollars

Written by Michael Fredman

Michael Fredman is a London based writer, editor and creative who has worked on web and print publications in fields as diverse as international politics, health and film.

The division between left and right is a no brainer

This is an article that I wrote for Creative Boom, part of The Guardian's Culture Professionals Network. All links open in a new window:

Are you a creative person, or are you a logical person? Chances are that if you are reading this you consider yourself a 'creative person'. If you were asked what side of the brain dominated your personality you would most likely say the right-hand side, for it is this hemisphere that in popular psychology is labelled as the creative, while the left is designated the logical, nerdy side. You can even look at a twirling dancer to supposedly test which type of brain you are the proud owner of.

The modern idea of a laterally divided brain is largely based on the findings of Roger Sperry, who won the Nobel prize in 1981 for his ‘split brain’ experiments.

However, as Ian McGilchrist (among others), points out, this simplification is no longer considered accurate by neuroscientists.The true nature of the brain is more complex than a left-right divide. Yet this generalisation perpetuates and extends to the distinction between art and science in the world at large. The caricature is that the world of the arts is entirely emotional and that of science is entirely logical, but is this necessarily so?

Take for instance the work of Leonardo da Vinci. It is well known that he drafted designs for a range of ingenious inventions, including a parachute, a tank - even a helicopter, and at the same time he drew and painted exquisite renderings of figures and scenes. Thanks to his inquisitive dissection of dead bodies, his art is alive with the tension of the musculature beneath the flesh. But was Leonardo a scientist, or an artist?

At the British Museum currently Grayson Perry, the Turner Prize winning artist, curates an exhibition entitled 'the Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman'. His work is placed alongside objects from the Museum's collection that he has selected for their resonance to his work and the themes he finds profound.

This exhibition is an example of how the logic of taxonomy, the painstaking archeology of fact, can co-exist with the emotional, personal - creative - world of the artist.

A Museum is a place more of logic than of art (even when filled with art). The British Museum in particular takes the sacred objects of other cultures and displays them to be viewed in a new context, removed from the spaces and times that confer specific meaning to them. The simple fact that sacred objects of one culture are displayed alongside sacred objects of another immediately negates the mythic power of each, where before they had claimed to hold the ultimate truth, the potency of alignment with God/Gods, in parallel they become examples and not the exemplar.

By introducing an artist as curator, the Museum makes us ask what is it that distinguishes a museum from a gallery. There are many similarities (reverence, silence, spatial layout, educative text etc.) yet they are distinct. And I think that part of this distinction lies in the creative/logical divide that exists at large in our society. I think that a Museum is, typically, a place that invites you to respond to objects and ideas with reason, where an Art gallery is a place that typically invites you to respond to objects and ideas with emotion.

Yet reason and emotion can co-exist. We live in an age of tremendous ideas, of scientific breakthrough. The large Hadron collider at CERN for instance, attempting through experiment to show us what exists in our universe at the elementary level. And here artists have been invited to participate. CERN has a program inviting creative people, artists, to a three month residency (new window) to explore and translate the science into art. Can art be scientific? Can science, logic, be art? A Mathematician may see great beauty in a formula and an artist may see great truth in form, but are they relatable?

Perhaps the simple fact that there is a common cause is enough, both the artist and the scientist are attempting to make sense of what is.

On the website of CERN’s artistic residency program the words of Einstein are used:

‘Knowledge is limited, imagination encircles the world.’

This is true and there is also a symbiosis: Imagination needs knowledge, to fire it into life, and knowledge needs imagination to innovate.

We are all of us neither left-brained or right-brained. We are whole-brained. Look at the dancer again, blink, and see if you can make her spin the other way. There you go. You are Leonardo da Vinci.

Copyright Michael Fredman 2012